manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Sept 5, 2008 10:17:00 GMT -5

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Sept 23, 2008 6:33:01 GMT -5

'We were the guinea pigs of punk'Eric's was tiny, overcrowded and short on girls, but it was the most thrilling nightclub in 1970s Liverpool. Frank Cottrell Boyce salutes its glory days Frank Cottrell Boyce The Guardian, Tuesday September 23 2008  Nearly everyone in the club was in a band ... Siouxsie Sioux and Jordan at Eric's in 1978. Photograph: Ray Stevenson/Rex Features A friend of mine recently jumped in a cab in Liverpool and asked to be taken to see La Princesse, the giant mechanical spider then menacing the Albert Dock. "Right ho," said the cabbie. "I love a bit of French situationism." He then went on to talk about les événements and Paris in 1968. Maybe the cabbie - his name was Rob Parr - was in Liverpool the last time situationism was big here, back in the late 1970s, when Ken Campbell would mount massive sci-fi epics and insist members of the cast wear their costumes on the way to work, to help break down the barrier between theatre and bus stop. Campbell, who died last month, was the dean of studies of a kind of countercultural university whose campus took in Liverpool's theatres (or their bars), Probe Records (or the steps outside the shop) and Eric's, a club whose brief, brilliant life is about to be celebrated in a new musical. Eric's was the most important punk club in Liverpool, a members-only, live-music venue at a time when live performance held all the cards. The best bands' records received limited distribution and little airplay, so you spent more time reading about them than actually listening to them. Every performance, therefore, promised a revelation, and not always in a good way. I remember pushing my way to the front at Eric's to see Iggy Pop, in the belief that I was about to behold a steaming great rock'n'roll Beelzebub. When the surprisingly tiny Iggy flounced onto the stage, someone shouted: "Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Mr Melvyn Hayes!" Iggy's resemblance to the It Ain't Half Hot Mum actor was as amazing as it was bathetic. But it wasn't as disconcerting as the night I saw the legendary Nico in the club, and told her I loved her. "Really?" she said. "Do you have any money? I seem to be a little short." I gave her one of my two 50-pence pieces - but she spotted the other one and, unable to bear her look of disappointment, I handed over my train fare and walked the 11 miles home. Eric's was tiny and dangerously overcrowded, but I remember hardly any trouble. Perhaps it was because the place attracted few girls (though the ones who were there were great), and therefore tended to empty out after the band had finished, as lads went off in search of women. It might also have been because of the popularity of pogoing as the dance of the day: the overcrowding meant that most people danced in the space-saving vertical dimension. The overcrowding also made the gap between audience and band, reality and possibility, seem more easily bridgeable. Nearly everyone in the club was in a band - but almost all the bands were imaginary. Making up a name and designing a button badge, even a poster, seemed to take priority over acquiring actual personnel or, indeed, instruments. One of the most important bands - the Crucial Three (Julian Cope, Ian McCullouch and Pete Wylie) - never actually played. Others would have been a lot better had they followed this example: Big in Japan, for instance, seemed to do nothing but stand on stage furiously yelling the phrase "Big in Japan" at the audience. But Big in Japan were only the second worst band on earth. Warsaw had a Bowie wannabe singer and were rubbish. One night they turned up with the same lineup but a different name. I saw right through the disguise and left, dragging my mates with me. The band's new name was Joy Division. If you hung around a similar club in Birmingham or Sheffield or Glasgow at that time, you would probably have similar stories. What was different about Eric's was the feeling that the music was part of some sort of cultural experiment, and that we were guinea pigs, or possibly pupils. Maybe it was the slightly patrician air of its owner, Roger Eagle, who was clearly on a mission to educate us all. The place is remembered as a punk club but in fact a very wide range of music - Stax, reggae, Cajun - was played there. Although I dine out on the great bands I saw at Eric's, the truth is I wasn't really that interested in the musicians. For me, it was more about the audience - being with people of my own age who were all suddenly aglow with the possibilities of their own creativity. And ego. Pete Wylie, for one, always gave the impression that he thought the Ramones, say, had come all that way from the US just to look at him. Mark Davies Markham, who has written Eric's - the Musical, puts it this way: "It was the inspirational place that working-class kids had been hoping for." He also says: "The day I discovered Eric's, my grey world turned Dayglo." I'd add that it wasn't just about working-class kids but everyone who thought life could be brighter. Many regulars ended up in bands that you will have heard of, some good, some bad, some banally successful, some magnificently wayward, among them Echo and the Bunnymen, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, The Teardrop Explodes, and on and on. And it wasn't just bands. People with an Eric's background ended up as politicians, community activists, fine artists, journalists, film-makers. I think perhaps that art's real function is to bring people together, and that it only has to be good enough to serve as a pretext for this. I don't know Markham, but it seems remarkable to me that we were both at Eric's unofficial opening night and here we are 30 years later, each about to open a show in Liverpool inspired by those days. Markham's is a musical about a man in crisis looking back to Eric's; mine (Proper Clever) is a flamboyant modern comedy, partly inspired by the fact that Roger Eagle arranged alcohol-free matinees at Eric's, so that youngsters like me could get a taste of that glorious moment. It's my way of saying thank you. The Christmas after Eric's was opened, I was offered a place at Oxford university. At the time, that didn't seem so different from being recruited by Nasa or appearing on Top of the Pops, but I hesitated - it seemed unthinkable to leave Eric's behind. When I mentioned this to a DJ at the club called Mike Knowler, he sat me down and told me that Eric's would be finished within a year and I'd be kicking myself if I didn't grab the chance. Which brings me back to that spider. Eric's raised the game of everyone who went there, and it did it without official help. The club was only possible because there was cheap real estate in the city centre, and because the punters didn't mind standing up to their ankles in urine when they used the toilets. In the end, it was closed down by the police in a raid: one night the club was suddenly filled with policemen and dogs and there was a panicked scramble for the exits. A young radio journalist, Christine Ruth, made a dash for the BBC's Merseyside studios to alert the nation. In those days, culture was in opposition to the economy. Now, culture works in partnership with the economy, and Liverpool's Capital of Culture year is expected to contribute to its prosperity. Watching the spider walk into the crowd on Albert Dock is the most excited I've been by a work of art since my Eric's days. But will that spider - thrilling as it was - inspire my children the way Eric's inspired me? Can you really have situationism by invitation? Would Mike Knowler have done what he did for me if he'd thought of me as a customer, rather than as a member of the same club? I'm asking because I want to know. I'm asking because I would really love to do it all again. · Eric's - The Musical is at the Everyman, Liverpool, until October 11. Box office: 0151-709 4776

|

|

|

|

Post by owen on Sept 24, 2008 16:55:12 GMT -5

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Oct 4, 2008 7:57:32 GMT -5

It was hailed as a great work of cinema - it made people cry

Terence Davies's new film rescues Liverpool from nostalgia and self-conscious parody

Ian Jack

The Guardian,

Saturday October 4 2008

I first saw Liverpool from the middle seat of a tandem in 1950. An eccentric way to approach the city even then, but every Sunday if the weather looked fine my parents would take the tandem from its shed at our home 30 miles to the east across Lancashire and we'd set off, with my older brother on his bike acting as an outrider. I remember green tramcars grinding smoothly through Liverpool's suburbs, my father shouting to my brother to watch out for his front wheel in the tramlines, and then sitting on a Mersey ferry where seagulls perched on the rail and I had a coughing fit because some crumbs from a roast beef sandwich had stuck in my throat.

1. Of Time and the City

2. Release: 2008

3. Country: UK

4. Runtime: 72 mins

5. Directors: Terence Davies

A whole day's excursion preserved in two scenes. Was there talk of Liverpool's bomb damage? Probably. Did we see ships? Certainly. But the grand narrative of the day has been lost. Departure, interesting incident, arrival, return: to make the picture more complete all these would need to draw on memories of other days out, or be invented.

This is what fiction usually does. One of the persuasive hallmarks of Terence Davies's films is that they recreate childhood as adults remember it, as sweet and occasionally sour fragments of a departed life. His best known, Distant Voices, Still Lives, evoked his own boyhood in Liverpool as the youngest in a working-class Catholic family of 10 children. It was made in 1988 and won all kinds of awards including the International Critics Prize at Cannes. But Davies made only three feature-length films in the subsequent 20 years. He became a "whatever-happened-to?" conversation piece rather than a working director, until this year, when Of Time and the City, his first film in eight years, was shown at Cannes. It was hailed as a great work of cinema, it made people cry, and it has re-established Davies's reputation as one of the handful of British directors with a singular and easily recognisable vision, in other words an auteur. From October 31 it can be seen at art-house screens all over the country.

It will be a success, perhaps even a small commercial triumph if audiences heed critics as they once did. Few people could have expected this. The film was made on a budget of £250,000, pulled together from various sources and dispensed by a committee organised under the flag of Liverpool's year as European City of Culture. Its description as "a documentary about Liverpool" hardly guarantees crowds beyond the city. To say that it re-creates an epoch of British history gets us nowhere at all, because that's what the British film and television industry does again and again. What makes Of Time and the City spectacularly different is the way it makes beauty out of our everyday pasts, so that what could have been easily been nostalgia or comedy or social history becomes an elegy for the way so much of Britain - not just Liverpool - was to our parents or ourselves.

In one way, its approach is as old as the British documentary movement itself: cinematic poems to working-class life began in the 1930s, and Davies credits Humphrey Jennings' wartime Listen to Britain as a particular inspiration. But Davies shot only a small proportion of his film - the scenes of modern Liverpool. Visually, it mainly represents a triumph of editing other people's work made over the past 60 years in streets, docksides, restaurants, trains.

Aurally, in its music and Davies's words, it rejects all the recent conventions that have governed how northern England is seen.

Once industrial cities have ceased to be generally important to the world - once their old purpose has gone - they often survive as a self-conscious parody; a two-dimensional cut-out assembled from football scarves, an intensified devotion to the local accent, cultural strategies and heritage trails, all in the name of identity and difference, and with an eye to tourism. In Newcastle upon Tyne, big men in black and white shirts sit in the stadium to tell us they are Geordies; in Liverpool, You'll Never Walk Alone, professional Scousers, The Beatles. From the moment Davies begins to read his script, you understand that these crude encapsulations are to be broken. He sounds like dons and actors used to sound - a grave voice, sometimes sardonic and at other times theatrical with loss. No trace of accent, other than RP. How could a poor little Liverpudlian grow up to sound like this? Soon, the question is shaming. How far are we imprisoned by modish ideas of "identity" even to ask it?

Then there are the words. A good deal of uncredited TS Eliot - mainly drawn from the Four Quartets and matched to pictures of all kinds of unlikely things, such as the Liverpool Overhead Railway and tugboats. But not only Eliot. Many half-remembered verses by other poets and from the Bible in a script cut and mixed as sharply as the footage it accompanies. Over modern scenes of girls lurching about outside a bar, Davies reads Walter Raleigh rather savagely: "Thy gowns, thy shoes, thy beds of roses/Thy cap, thy kirtle, and thy posies/ Soon break, soon wither - soon forgotten/In folly ripe, in reason rotten."

Not least, there is the music. Davies, who left school at 16, was working as a young shipping clerk when The Beatles began. He devotes only a few seconds to them, mourning the departure of the '"witty lyric and the well-crafted love song" as he turns instead to Sibelius, Bruckner and '"every over-wrought note" of Mahler. Great music can give almost any scene the pathos or majesty that intrinsically it may not deserve - Woody Allen called it "borrowed grandeur" - but Davies often uses it to forgivable effect. To an aria by the Romanian composer Popescu Branesti, he cuts nearly 20 scenes of domestic life in the terraced streets of 1940s Liverpool. A boy delivers milk on a bike; a woman lights a coal fire; a girl combs her hair; a man shaves; a housewife scrubs her front step; children rush towards a playground maypole ... and all these small acts are invested with a dignity that honours the people who performed them.

The mood changes with the coming of the municipal tower block and the dole. "We had hoped for paradise," Davies says. "We got the anus mundi." And then it changes again with the present, where floodlights play on the Liver Building and deconsecrated churches have been made into restaurants "as chic as anything abroad". He wonders, "Is this happiness? Is this perfection?"- questions that will now need to be supplemented with "And in any case, how is it afforded and how long can it last?"

It isn't a perfect film. It declines, I think, whenever the lens leaves Liverpool. Scenes from the Korean war are matched heavy handedly (and given Davies's tastes, peculiarly) with The Hollies and "He's not heavy, he's my brother." The Queen Elizabeth's coronation prompts some political sentiment about rich and poor, but when Davis calls it "the Betty Windsor show" it could be Kenneth Williams having a try at republicanism. Williams was one of Davies's heroes, when, as a boy filled with homosexual longing, he turned on a radio "as small and brown as Hovis" to hear all that Julian and Sandy palaver on Round the Horne.

But if these are flaws, they should be forgiven. Davies has elevated the common British working-class experience out of folksiness, sociological inquiry and football and given it a proper send-off with TS Eliot, Mahler and all. It became history in my lifetime. Watching the film, seeing from above crowds pour off the ferries like purposeful black insects, it was strange to think that as a small boy, the same age as Davies, I had been part of all this one Sunday, before we turned the bikes round for home.

|

|

david

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by david on Oct 4, 2008 8:53:31 GMT -5

I'm just looking over the festival schedule. I have to choose between Gomorra and Of Time and the City. I'm leaning to Gomorra, because I think the Davies' film is the more likely to get a shown in a regular cinema here. It kind of sucks, because I'd like to be sure of seeing both . . .

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Oct 4, 2008 9:06:28 GMT -5

yeah, go for gomorrah, i have a feeling about it. and remember, it's all true. it really happens like that in today's italy (well, napoli...).

|

|

|

|

Post by dino on Oct 24, 2008 2:11:03 GMT -5

fucking hell manh-olo... are you the Catanese who won 100 millions of euro?? please send me just a couple of millions

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Oct 24, 2008 4:38:30 GMT -5

it wasn't me but something strange happened. i never play the game but before the previous draw (on tuesday) a friend of mine said, let's do the lotto today and we picked out a few numbers for a couple of euro and lost. it was the first time i'd played in about 12 years. the next fucking draw (yesterday), what happens? some guy wins it from the tobacconist round the corner frm where i live. five minutes walk.

100 million dollars.

|

|

|

|

Post by dino on Oct 24, 2008 4:40:37 GMT -5

christ. what a story

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Nov 1, 2008 17:45:41 GMT -5

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Dec 14, 2009 16:39:37 GMT -5

here's something interesting. in the mid 60s ken loach made a series of films for bbc tv. one of them was called "the golden vision" and was based in liverpool. you can check it out on youtube: www.youtube.com/results?search_query=the+golden+vision&search_type=&aq=fthe writer, neville smith, also wrote the screenplay (and original book) of gumshoe. an 70s film also set in liverpool and starring the truly great albert finney. directed by stephen frears. quality stuff. check it out if you see the dvd in the $2 bin. neville smith is the only famous guy who went to my high school. |

|

|

|

Post by dino on Dec 15, 2009 8:35:16 GMT -5

did you survive the tromba d'aria?

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Dec 15, 2009 14:54:08 GMT -5

"did you survive the tromba d'aria?"

yes. it was nothing special, we get a couple every year. if your name's written on it you have to go quietly but they usually only kill one or two people. more dangerous crossing the road.

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Jan 10, 2010 5:34:36 GMT -5

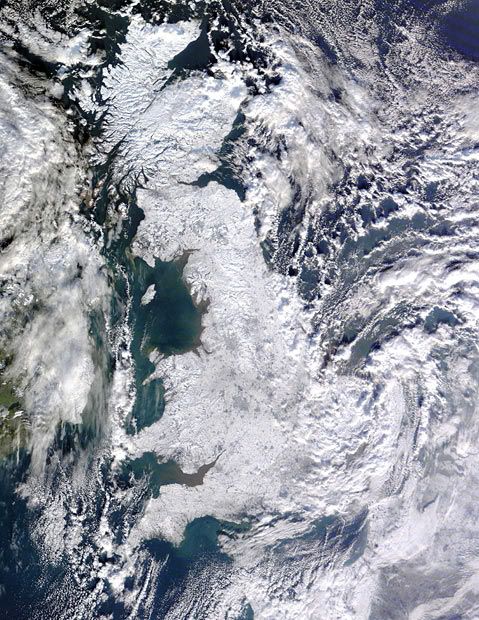

britain yesterday:  takes me back...  foto from the early 50s. many roads in liverpool slope down to the mersey and heavy snow is pretty cool for the kids. the road i grew up in looked pretty much like this one (which is actually in birkenhead, but you get the idea). |

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Jun 11, 2010 5:06:25 GMT -5

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Jul 11, 2010 12:54:22 GMT -5

the odeon cinema exactly ten years before boby hit town:  |

|

digit

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by digit on Sept 26, 2010 15:36:48 GMT -5

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on May 15, 2011 5:25:26 GMT -5

|

|

digit

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by digit on Jul 17, 2011 12:52:28 GMT -5

|

|

manho

New Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by manho on Jul 17, 2011 14:16:18 GMT -5

imagine merseybeat without the beatles...

|

|